8 minutes

Getting Started with Pester

Written on Ubuntu with PowerShellCore.

Pester is a PowerShell behavior-driven development (BDD) style testing framework. But, really all you need to know about it before getting started, is that it’s a testing framework and it can be used to automate the testing of your PowerShell code. You might think to yourself well what’s the point of that? I already wrote my PowerShell function, all I need to do now is run it and see if it does what I want. That’s called testing the code and is exactly what Pester can do for you. To put it in perspective a little, you probably learned PowerShell so that you could automate and have the computer do things for you. Why not learn Pester and have the computer do the testing for you as well?

Installing Pester

If you’re running Windows 10 or Windows Server 2016, you already have a copy of the Pester PowerShell module. However, like all modules and software for that matter updates are released so you’ll want to grab the latest versions. To do that use the following command. The current version is 4.0.5, at least at the time of writing this blog post.

Find-Module pester -Repository psgallery | Install-Module

Creating Pester Tests Files

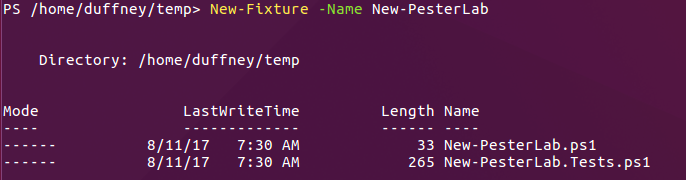

Now that you’ve installed the module it’s time to create the Pester test files. Pester has a cmdlet called ‘New-Fixture’. This cmdlet generates a function PowerShell script and another PowerShell file that contains the tests. For this blog post, I’ll be creating a new function called New-PesterLab. To create the PowerShell script and its accompanying test use the following command.

New-Fixture -Name New-PesterLab

After you run the command you’ll notice two new files. New-PesterLab.ps1 and New-PesterLab.Tests.ps1, New-PesterLab.ps1 is the PowerShell script for the function I’ll write and New-PesterLab.Tests.ps1 is the PowerShell script for the Pester test I’ll write. It’s highly recommended you follow the naming scheme FunctionName|ScriptName.Tests.ps1. Once reason for that recommendation is it’s easy to keep track of what tests go with what function or script file. The other reason is by default Pester will run all .Tests files when pointed at a directory.

sidenote: You don’t have to use the New-Fixture cmdlet, if you already have a function file you can just create the function.tests.ps1 by hand, but it won’t have any pester syntax in it.

Writing the Function

Next, open the New-PesterLab.ps1 update the code to what is shown below. The New-PesterLab function now accepts two parameters $Path and $Name. These two parameters are used to; create a folder, create a file and set the content of the new file. It’s a really simple function, but that will make it easier to understand how to write pester tests for it.

function New-PesterLab ($Path,$Name) {

New-Item -Path $Path -Name $Name -ItemType Directory -Force

New-Item -Path "$Path\$Name" -Name "$Name.config" -ItemType File -Force

Set-Content -Path "$Path\$Name.config" -Value 'Pester is Pretty Awesome' -Force

}

Introduction to Pester Scripts

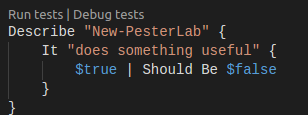

Now that we have a function to test, it’s time to write the test, but before that let’s take a look at the new pester test we created. After you open the New-PesterLab.Tests.ps1 you’ll notice it already has some code in it. The first three lines might look confusing to you so let’s take a closer look at what it’s doing.

$here = Split-Path -Parent $MyInvocation.MyCommand.Path

$sut = (Split-Path -Leaf $MyInvocation.MyCommand.Path) -replace '\.Tests\.', '.'

. "$here\$sut"

Notice that it’s creating two variables $here and $sut. $here is being populated by Split-Path -Parent $MyInvocation.MyCommand.Path. Which is a fancy way of getting the current path of the script being executed. In this case since my New-PesterLab.Tests.ps1 is located at /home/duffney/temp, so that’s what $here will be populated with. Moving on to $sut, it is being populated by this code (Split-Path -Leaf $MyInvocation.MyCommand.Path) -replace '\.Tests\.', '.'. It uses the same path $MyInvocation.MyCommand.Path, but it used a different parameter -Leaf. The -Leaf parameter indicates the Split-Path cmdlet should only return the last item in the path. So if the path is /home/duffney/temp/New-PesterLab.Tests.ps1 it will just return the end of it New-PesterLab.Tests.ps1 That output is then passed to the -replace operator and .Tests. is replaced with . resulting in New-PesterLab.ps1. In programming sut means system under test. Which makes sense because New-PesterLab.Tests.ps1 is the function we are going to run tests against. The third line . "$here\$sut" simply combines the two variables and dot sources the function into the PowerShell session. Let’s now move on to lines 5-9, the Pester part of the script.

Tip:The easiest way to see the variables is to put a breakpoint somewhere in your test script and hit F5 (in Visual Studio Code) to run the debugger. At that point the variables will be exposed through the debugger make it way easier to find the values.

Describe "New-PesterLab" {

It "does something useful" {

$true | Should Be $false

}

}

Line 5 starts with a Describe block, this is a command that comes from the Pester module. It is used to for the lack of a better word Describe the test. Every Pester test has to have at least one Describe block. I say Describe block, but it’s really a PowerShell cmdlet. If you run help Describe you’ll get some comment-based help explaining the parameters etc.. The Describe block in this example is taking a positional parameter Name with the value New-PesterLab and then it starts a script block with{}.

In side that Describe block is another Pester command It. The It commands are used to test your code and the Describe is more of a container to hold all the tests. The It block is also taking a positional parameter of Name with the value does something useful and then a script block. Inside that script block is the actual test logic. In this case it is testing to see if $true is $false. The actual code for this is $true | should be $false. Should is another pester command that defines an assertion. Just think of assertion as test for now. There are several options available with the should operator. Be as seen in this example is just one of them. Be compares one object to another for equality and throws and error if they are not the same. For more information on the Should operator checkout the Pester wiki.

Writing Pester Tests

Now, it’s time to actually write some tests! But… what do we test? Well, what would you test if you were running this function and testing manually? Looking back at the code it does three things; creates a folder, creates a .config file and sets the value of that config file to a known value. These are the three things we want to test. Let’s start with testing the creation of the new directory.

How would you test the existence of a directory with PowerShell? Once answer to that question is to use the Test-Path cmdlet. Test-Path returns a true or false so testing that is easy. Let’s update the first It block to reflect this.

Describe "New-PesterLab" {

It "New Directory Should Exist" {

(Test-Path -Path $Path) | Should Be $true

}

}

Next let’s write a test that makes sure the .config file is created. To test the existing of a file in PowerShell we can use the Test-Path cmdlet again and add a second It block to our Pester test.

Describe "New-PesterLab" {

It "New Directory Should Exist" {

(Test-Path -Path $Path) | Should Be $true

}

It "app folder should exist" {

(Test-Path "$Path\$Name") | should be $true

}

}

Lastly, we should test the value inside the .config file. We know the value should be Pester is Pretty Awesome so we can use the Get-Content cmdlet to return the value and then pass it to the Should operator. The Pester test now has 3 it blocks resulting in 3 tests. One more thing we have to do before we can run the Pester tests is call the function inside the describe block. . $here\$sut only dot sources the function in it doesn’t call it. To call the function we simply have to provide a path and a name parameter to New-PesterLab. Noticed that it’s before all the It blocks but inside the describe. It’s now time to run the Pester tests, but how?

Describe "New-PesterLab" {

$Path = '/home/duffney/temp'

$Name = 'pesterapp'

New-PesterLab -Path $Path -Name $Name

It "New Directory Should Exist" {

(Test-Path -Path $Path) | Should Be $true

}

It "app folder should exist" {

(Test-Path "$Path\$Name") | should be $true

}

It ".config file value should be Pester is Pretty Awesome" {

(Get-Content -Path "$Path\$Name.config") | should be 'Pester is Pretty Awesome'

}

}

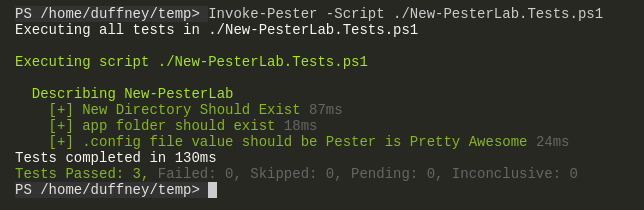

Running Pester Tests

At this point you have a function and a Pester test. It’s now time to run the Pester tests. The command to execute Pester tests is Invoke-Pester. You can learn more about this cmdlet by reading the help file Help Invoke-Pester. After reading the help you’ll notice the first parameter is Script. The script parameter accepts a single script or multiple scripts. Script of course is referring to the Pester test script not your function. To run Pester against our newly created scripts issue the following command.

Invoke-Pester -Script ./New-PesterLab.Tests.ps1

You’ve now successfully written and execute a Pester test congrats! Even with this really simple example of creating folders and files Pester was able to save you some time. There is a lot more to Pester, but I hope this blog post opened your mind up to the realm of possibilities with Pester.